Whiplash as a Central Nervous System Pathology

Stress, concussion, and chronic pain.

What is whiplash?

If you asked an average person to define whiplash, they would probably say a neck injury from a car accident. While they would not be wrong; there is far more complexity to what structures are damaged during a whiplash injury, as well as the plethora of symptoms that appear afterward. Whiplash is not simply neck pain – and it is not always caused by a car accident.

Whiplash was clinically termed Whiplash Associated Disorder (WAD) in 1995 by a Quebec Task Force to characterize a set of somatic and emotional-behavioural symptoms arising from cervical injury caused by a Motor Vehicle Collision.2 Now, wait just a minute. Did we not just say that whiplash is not necessarily caused by a car accident? Yes, we did. As clinicians, we suggest that the 1995 definition needs to be re-examined, as there are plenty of whiplash-type injuries that present clinically, and not all of them have been caused by a motor vehicle collision. (And, because there is no formal term besides ‘whiplash’ for the unique set of clinical symptoms experienced after a whiplash-type injury, we must therefore refer to it as whiplash, regardless of the cause).

Whiplash is diagnosed using a classification system ranging from zero (least severe – no symptoms) to four (most severe – fracture or dislocation). Basically, you could have a whiplash diagnosis with hardly any symptoms present, or you could have a broken neck, or you could have anything that lies in between the two. Another unfortunate aspect of whiplash is its potential for delayed symptom onset. Many patients feel totally fine after an accident, only to experience pain and dysfunction a few hours to a few weeks later and not understand where it is coming from. Therefore, it is understandable why whiplash injuries are some of the most controversial medical diagnoses, due to the sometimes-bizarre timeline of symptom onset, the broad range of symptoms, their variance in severity, the difficulty in objectively measuring the number of visible lesions upon medical imaging, and the level of pain not always corresponding with the size and/or location of those lesions. The fact that X-ray is typically ineffective in 90% of whiplash injury cases, due to the injury predominantly impacting soft tissues over bone, is also unhelpful.2 The diagnostic process is additionally impacted by the patient’s subjective assessment, which is sometimes impeded by inexplicable neurological factors, stress, and pressure from the insurance claims and legal process.

What causes whiplash?

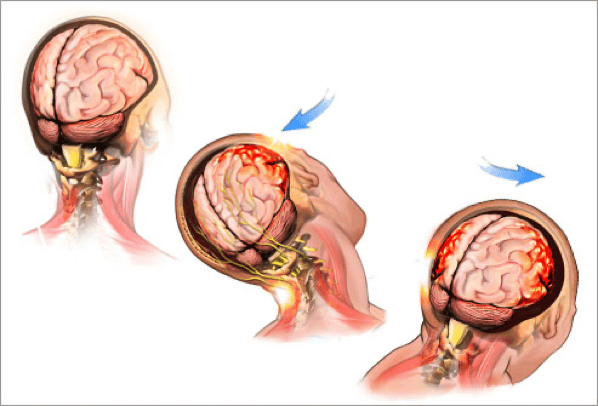

A lot of things can cause whiplash; however, their Mechanism of Injury (what bodily movement physically causes them) is usually a rapid and forceful jarring of the head back and forth on the neck and shoulders, like the tip of a whip when it cracks.1 While rear-end car accidents are usually the most common cause of whiplash, the injury can occur in many other ways as well. A heavy body check or tackle in sports, a slip on the ice, assault, ATV accidents – even an extra-zealous trip on a boat or an amusement park ride – these are all activities that can cause a whiplash-type injury; sometimes without the patient being fully aware that it ever happened.

What physical injuries occur during whiplash?

There are several theories about how the damage occurs:

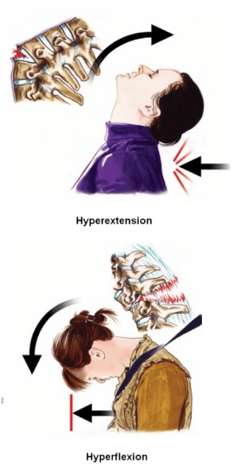

- Hyperextension (& Hyperflexion) Theory:

Your body lurches forward while your head, which is not strapped into a seat, remains in place for a second before being thrown forward with the rest of your body. This aggressive motion can cause physical damage to the vertebral bodies in the cervical spine, as well as their attachments. Possible injuries observed would be severe ligament sprains with potential avulsion injuries around the anterior edges of the vertebrae, overstretching of the nerves and muscles in the neck and throat, crushing of the articular column, range of motion deficiencies and a sense of instability, fear of movement due to facet joint injury, and microbleeding within the vertebral joint synovial fluid.2 The pain experienced would be deep and may feel structural and sharp over achy muscle soreness. (It may also be both). Patients may feel pain upon speaking or swallowing, with significant pain and range of motion issues coming from deep within the neck.

NOTE: if you have been in an accident and are having difficulty swallowing (or feel like there is a lump in your throat), stop moving immediately and call 911. This can be a symptom of a broken neck or dislocated vertebrae and it could be serious.

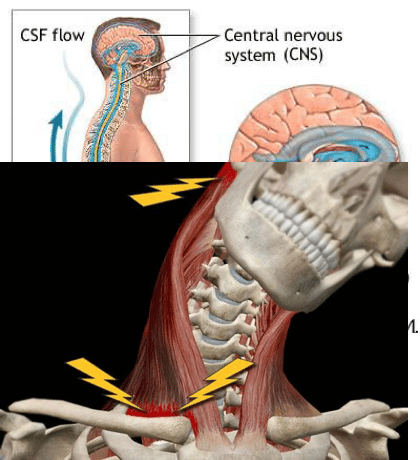

Hydrodynamic Theory:

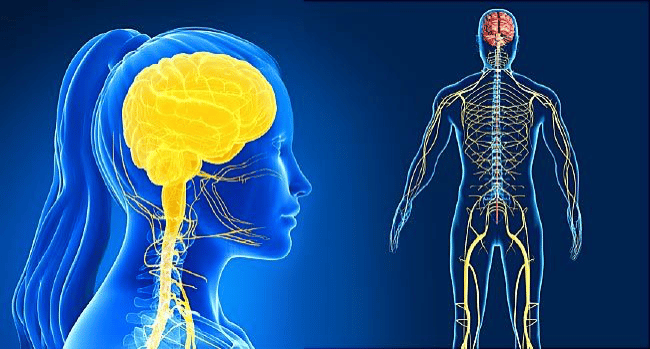

This is the concept that our cerebrospinal fluid is forcefully displaced under pressure during a collision,

causing it to rush rapidly through the cranium and root sheaths of the spine. This is a legitimate explanation for neurological symptoms that arise after a collision, including upper limb paresthesia and central nervous system disorders. This could explain why many patients experience depression and anxiety, behavioural changes, balance and coordination issues, and inability to concentrate after being injured in a car accident.2

Stress as an aggravating factor in Whiplash Associated Disorder

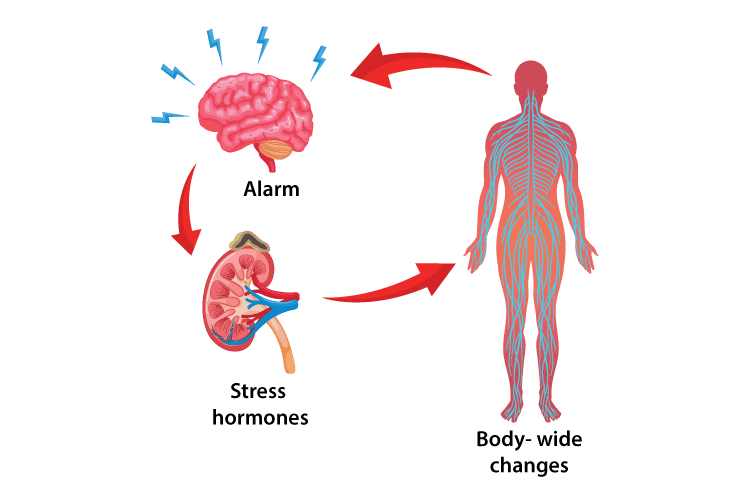

Another interesting layer to the whiplash theory is the concept of a sudden stress response contributing to an exacerbation of symptoms following the injury. One researcher found that an abrupt scare could be a prerequisite in the development of whiplash symptoms, as 78% of whiplash patients in his study did not see the collision coming and were surprised upon impact.3

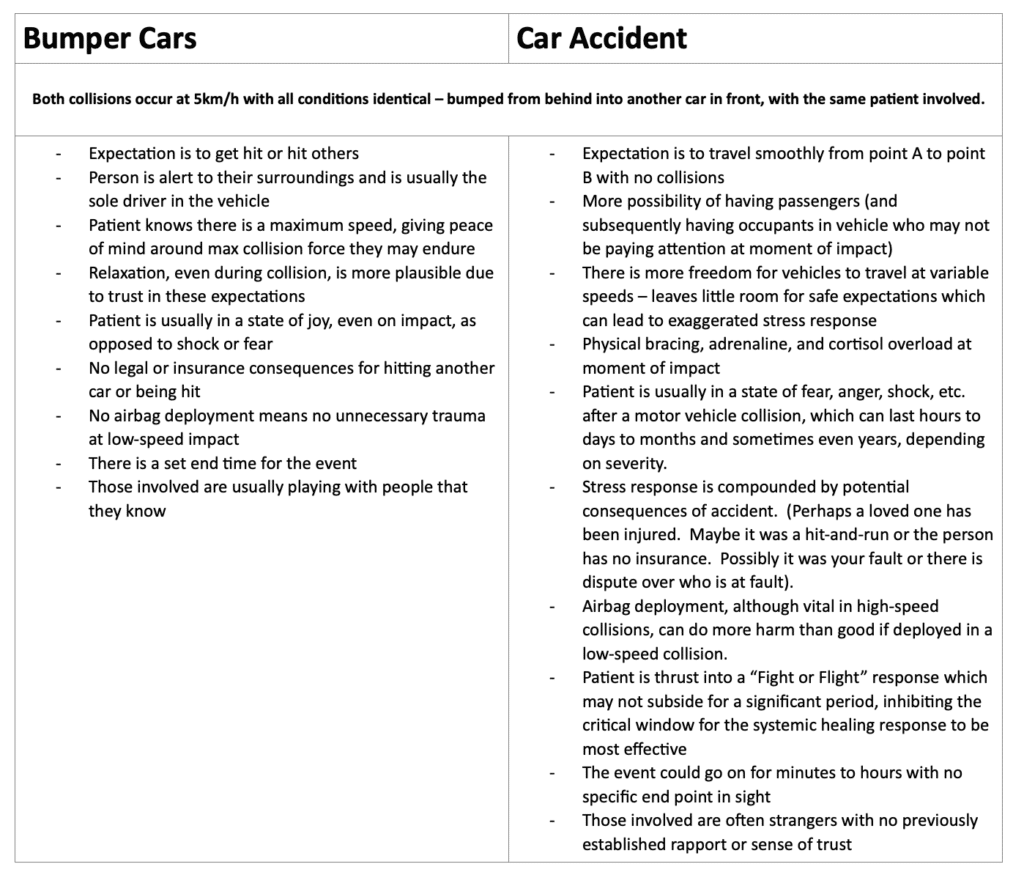

Furthermore, the unexpected outcome of a collision situation can also play a role in the disproportionate size and length of the stress response that may occur. This could explain why a person who endures the exact same degree of forces while playing bumper cars may never experience the same level of pain or dysfunction as someone in a fender bender.

There are some key differences between the two situations which could be playing a role in magnitude of the stress response and subsequent injury:

Regardless of what caused it, chronic whiplash patients are observed to experience injury and dysfunction in the brain and spinal cord that can cause hypersensitivities in extensive, completely unaffected areas of the body. In many whiplash cases, multiple medical images of the neck have failed to show any traumatic tissue injury in both acute (new) and chronic (old) phases of injury, regardless of significant pain being present. As previously mentioned, whiplash injuries seem to occur at ranging severities, regardless of the speed of impact, with either a weak or no “dose-response” relationship from the magnitude of impact to the severity of the outcome.3 Another study noted that whiplash associated disorder seems to present in similar fashion to other musculoskeletal conditions where the patient is exposed to a stressful stimulus at the moment of injury. The repercussions from this can include increased sensitivity to pain, changes in perception of physical touch and hot/cold sensations, difficulties sleeping, emotional distress, and depression.2

The connection between whiplash, concussion, and chronic pain

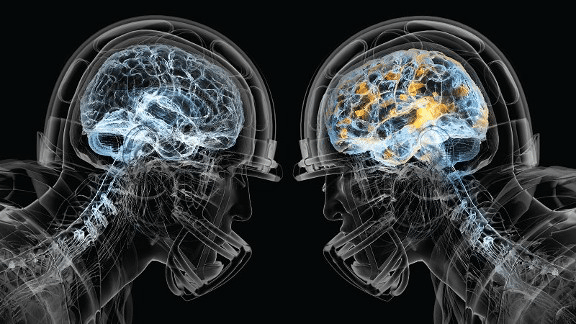

A concussion is a mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI).11 There is evidence to suggest that the majority of whiplash patients have also suffered a concussion. When we think of the mechanism of injury for concussion and whiplash, it makes sense that we should be assessing and treating for both when there is confirmation of one present.

Even minor whiplash patients can produce symptoms like those experienced by concussion patients. This tracks when we consider that a concussion is the result of the brain being rattled around inside of the skull. While it is normally there to protect us from outside forces, it is ultimately the skull that causes the damage to the brain upon impact. Perhaps more aptly named, a concussion is like ‘brain whiplash’ – the brain keeps moving when the skull stops, slamming it into the bones of the inner skull before twisting and recoiling backward into the other side. This can cause multiple impacts on the brain. Some patients will experience chronic headache, widespread body pain, sleep disturbances, and mood changes after a concussion11.

In the last decade, some staggering statistics have emerged regarding neurodegenerative diseases in retired National Football League (NFL) players being significantly higher than the general population. By significant, the mortality rates for specific conditions were 3 and sometimes 4 times higher than the control group. The correlation was believed to be the amount of repetitive head injuries players in these sports suffered relative to their civilian counterparts.14 Typical causes of death noted in one 2012 study

were Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS.14; however, depression, dementia, rage, violence, and suicide have also been described as possible outcomes of what we are now beginning to understand as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). CTE is a fatal, degenerative brain disease caused by repeated head injuries over time. It can only be diagnosed with an autopsy of brain tissue at this time.15 While the current understanding is that not everyone who experiences head injury will develop CTE, it is commonly found in patients with frequent head trauma, such as athletes, military personnel, and those working in physical jobs or transportation fields.

frequent head trauma, such as athletes, military personnel, and those working in physical jobs or transportation fields.

We have also discovered that both whiplash and concussion patients often experience chronic, unexplained, referred pain globally through their body after injury. This is referred to as pain chronification and has a lasting and profound impact on quality of life. Based on this knowledge, it is imperative that concussion history be clearly documented and appropriately managed, accounting for each of the previous traumas that came before. This sounds straightforward but becomes far more complicated when we consider that a large portion of whiplash patients, which are often positive for concussion, go undiagnosed. Some studies suggest that a strong connection exists between whiplash injury and long-term dysfunctional neuromotor control.3,4 This is supported by disrupted muscle activation patterns, tensing of accessory muscles for primary use, and uncoordinated head, eye, and upper limb movement patterns after a collision. 3,4 Behaviourally, it is not unusual to note character changes, such as increased anxiety, fear, aggression, withdrawal, and anger after a whiplash injury.2 That sounds eerily like concussion cases and could explain the long-term chronification of pain in patients, both diagnosed and undiagnosed, for one or both injuries.

A thought-provoking article published in the Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy in 2019 explores the possible connection, or at least similarities, between whiplash injuries and concussion, while also shedding light on the concern that there is no definitive “gold standard” diagnostic test for either. Furthermore, the treatment guidelines for both are developed and implemented separately, leading to misdiagnosis, delays in appropriate care, and impaired patient outcomes.10 Recommendations included amalgamating whiplash and post-concussion protocols and incorporating screening for post-concussion symptoms after a motor vehicle collision10. We also suggest baseline measurements be taken as soon as possible in life; this may require policy change for public health care. This can give a better comparison for accurate assessment on a patient’s true pre-injury health status for future reference. We also recommend that these standardized measurements should become a regular part of a physical, to help determine onset of any neurological condition that may otherwise go unnoticed until it has progressed significantly.

What constitutes a ‘full recovery’?

Clinically, a full recovery is defined as “a full return to pre-injury condition.” You must be able to complete all aspects of your life prior to the accident for your recovery to be considered comprehensive and complete. Whiplash injuries can resolve quickly; however, studies and clinical experience have shown that 20-40% of whiplash injuries will become chronic, which means the pain persists longer than 3 months after the accident. One study noted that 40-68% of whiplash patients with moderate to severe symptoms will still make a full recovery within one year, leaving 32-60% who will not.2

Evidence suggests that whiplash injuries are 40% more likely to become chronic than sprains or strains that have occurred elsewhere. 3 Immediate and aggressive treatment of whiplash injuries (as if they were a strain/sprain elsewhere in the body) was ineffective and actually slowed down recovery times for most patients. 3 Current research for concussion rehab, indicates that too much mental and physical rest after a concussion can contribute to prolonged concussion recovery and can extend the patient’s time experiencing PCS symptoms.13 Consequently, we can begin to see the importance of maintaining a delicate balance of care in order to effectively rehabilitate both injuries at once. The process requires careful selection of appropriate methodologies and modalities, used on the correct systems, in the right doses, at the right times. This supports the notion that whiplash may more likely be a slowly evolving pathology of the central nervous system, rather than a sudden, traumatic sprain or strain of the soft tissue.3

If the theory that all whiplash patients are also concussed holds true, the concept of “full recovery” could change for whiplash injuries in the future. We are only recently starting to learn about the cumulative, long-term, degenerative effects of concussion on perception of pain, behaviour, and overall quality of life. Until relatively recently, concussion injuries were considered minor in comparison to other musculoskeletal conditions, with full recovery considered possible even sooner than a muscle strain. Today, while we can say that recovery is possible from concussion, we can also argue that there is long-term irreparable damage caused by it, with potential for intensifying symptoms over time and/or development of CTE.14 In cases with recent head trauma, severe impairment comprised of a range of symptoms can occur (known as Post Concussion Syndrome, or PCS). Interestingly, one study noted that psychological intervention for PCS patients shortened the length of time they suffered from the syndrome. More research is needed in these areas to fully understand the long-term effects of concussion relative to the stress response and pain chronification after whiplash, but we can safely suggest that they become a key part of the same conversation.

Getting a concussion is easy, testing for it can be difficult, recovery is time-consuming, and the athlete may never fully return to baseline or pre-injury condition. In many cases, there is no baseline measure taken to begin with – so what even is ‘pre-injury’ condition for these individuals? We are making educated guesses, at best. The effects in youth sport are even more detrimental when we consider the potential for concussion impeding long-term brain development which, as current literature supports, occurs until approximately 25 years of age. These new discoveries have changed the face of certain sports, such as hockey and football; from their rule books and equipment requirements, to the valued skillsets of their players, to their rehabilitation programs.

We must start paying closer attention to whiplash injuries in the same way, regardless of how they happened. Whiplash is common, concussion is common, and both are typically caused by the same type of motion – but they are frequently diagnosed as one or the other, not both. You do not have to suffer an actual blow to the head to get a concussion. Whiplash patients may come for care with no concussion diagnosis; however, whiplash is arguably the secondary injury that should be addressed, with concussion protocols being integrated as the primary care priority.

When whiplash becomes a syndrome or disease

Whiplash disease has been termed a post-traumatic condition; but it could also be explained as an evolving pathology, caused by a whiplash injury to the neck accompanied by persistent, long-term symptoms.3 After discussing the possible aggravators of whiplash disorder, particularly concussion, it becomes easier to understand how everyone seems to recover from whiplash differently, especially if they pursue only one form of treatment or are misdiagnosed.

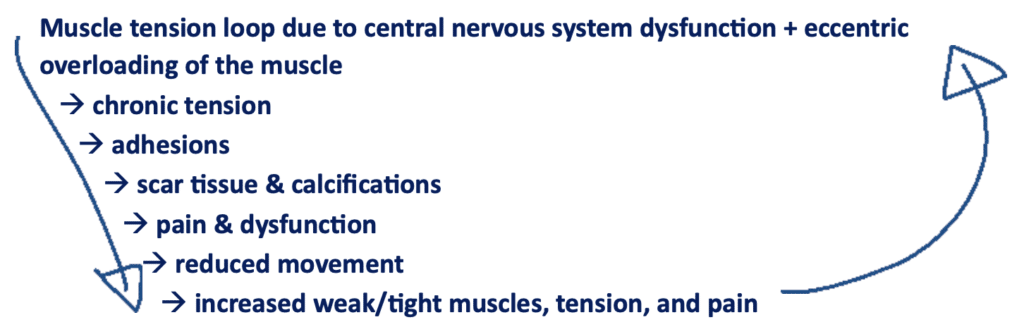

Initial tissue injuries may contribute to the acute symptoms patients experience; however, central nervous system dysfunction over time causes an overall lowered pain threshold contributing to an extremely high sensitivity (and possible response) to pain.3 Because of the long-term neurological nature of the symptoms experienced by many whiplash patients, some clinicians have suggested that whiplash is a disorder of the central nervous system over being a traumatic peripheral tissue disorder.3,4 This would support the theory that whiplash patients are also experiencing concussion. This is due to the lack of correlation between areas of pain and the actual location of lesions on medical imaging, issues with muscle coordination, eye tracking, and motor control, and the abnormal muscle activation and tensing patterns that occur afterward. Upon latent medical imaging, chronic whiplash cases will often show higher levels of fat deposits and muscle atrophy because of the injury impairing long-term function in the patient.2 This creates a cycle of dysfunction that can contribute to further musculoskeletal problems as time progresses.

The Progression of Whiplash into Myofascial Pain Syndrome (MPS)

“As the twig is bent, so grows the tree.” – Alexander Pope

While Pope was making a reference to child psychology, the saying rings true for the progression of myofascial pain syndrome. The initial stimulus may be small, but the progression of whiplash can evolve in a way that it creates more problems along the way:

Unfortunately, once scar tissue has formed and dysfunctional movement patterns are present, repairing the system is not a simple act of stretching out chronically tight muscles or strengthening those that have atrophied. They will immediately return to their pathologic state; treatments and exercises might even cause significant discomfort or injury. The key is to reset the muscle pattern and remove scar tissue to allow for the system to relax enough to heal correctly. If the patient has struggled for years in this pain loop, they may have other aches and pains that have cropped up from compensatory movements over time. These also must be addressed in order for the patient to make the best possible recovery.

Treating chronic whiplash using extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT)

Analysis of a collection of studies has shown shockwave to be an effective, low to no risk, non-invasive approach to managing acute and chronic injuries, while also avoiding the negative side effects of invasive procedures, such as surgeries and injections. In many cases, pain levels in patients with myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) following shockwave therapy were below that of other therapy methods, specifically: trigger point injection, dry needling, and ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency. As pain chronification in whiplash is likely caused by the fallout from concussion and the delayed onset of myofascial pain syndrome, it could respond quite favorably to shockwave treatment.7

As whiplash often presents and progresses through both acute and chronic stages, it makes sense to use shockwave as a modality in the healing process as it works well on injuries in all phases. The technology is a novel approach to whiplash care that has gained traction in North American clinics in the last decade for a few reasons:

- It is painless and non-invasive

- Nociceptive properties often provide pain relief upon treatment

- It is time and cost-effective (only 3-4 treatments are usually required)

- It stimulates simple and safe scar tissue removal, new blood vessel growth and stem cell activation

- It stimulates cellular communication to reset the neural pathway from the pathologic tissue to the brain

- It is often effective where other therapies have struggled (but usually complements their results beautifully)

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy has become so popular that many insurance companies recognize and cover shockwave services under extended health benefits plans and/or in chronic pain cases from collisions. One study published in 2021 determined that shockwave therapy was more effective at treating myofascial pain symptoms than ultrasound, home exercise and heat therapy, particularly in Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores after 4-week follow up.8 This is not to say that these other therapies do not work. In fact, a combination of these in conjunction with shockwave would be ideal. The key is that shockwave therapy treatment may play a vital role in ‘unlocking the door’ on the body’s ability to heal the tissue and the subsequent the efficacy of other treatments.

Treating Neurological Disease with Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy (ESWT)

Currently, there is limited research to support ESWT as an effective therapy for the treatment of neurological and neurodegenerative disease, such as Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, ALS, and CTE. That being said, there is preliminary evidence, in some clinics using electrohydraulic shockwave devices, to suggest that ESWT could be an effective treatment option to at least manage the symptoms of many of these conditions. Given the increased prevalence of neurodegenerative disease in the global population, a shift in ESWT research focus towards these conditions, and their precursors (such as concussion and whiplash), would serve well in the future.

Discussion & Recommendations

The newest evidence suggests that a combined multidisciplinary approach using guidelines for both concussion and whiplash protocols be implemented for patients responding poorly to rehabilitation for whiplash injury.10 We further recommend that diagnostic and treatment protocols for whiplash be merged with those for concussion management as soon as possible for a more streamlined and effective approach to care. Post-traumatic stress counselling and/or psychological services should be a mandatory part of recovery, as patients exposed to emotional stress at moment of injury may develop more exacerbated symptoms, particularly if left in a prolonged state of stress. Further research is needed in this area to fully understand the effect of a sudden stressful stimulus at moment of impact.

Based on the available research, it is possible that every whiplash patient is also concussed. As such, we recommend every whiplash patient should be treated as if they have a concussion, whether it is diagnosed or undiagnosed. This is supported by the observable long-term disordered central nervous system patterns and pain chronification after whiplash mirroring that in concussion patients. We also strongly recommend that CTE studies include chronic whiplash patient populations in their analyses.

A combined multidisciplinary approach is recommended for the most comprehensive recovery after whiplash. Areas of treatment would ideally include:

- Concussion protocols

- Vestibular stimulation

- Cognitive exercises, such as memory and concentration games

- Balance exercises

- Visual tracking exercises

- Neuromuscular activities and fine motor control exercises

- Psychological counselling for mitigating stress response and sleep disturbances

- Conservative, non-invasive MSK rehab initially, including gentle manual therapy in first 72 hours, followed by a full shockwave protocol before the onset of Myofascial Pain Syndrome.

For shockwave therapy treatment, research focusing strongly on neurodegenerative conditions would be highly beneficial. It is likely that individuals who experience chronic head injury, particularly in conjunction with stressful stimuli, are at an increased risk of developing pain chronification and neurodegenerative conditions later in life, such as Alzheimer’s, ALS, Parkinson’s, MS, and CTE. Shockwave treatment could not only be used for the treatment of soft tissue injuries immediately after the collision but may also play a vital role in long term maintenance of central nervous system health and prevention of neurological degeneration. More research is needed in this area; however, shockwave therapy is proving itself as a low-risk treatment option for both acute and chronic phases of whiplash and concussion without any negative side effects. Earlier treatment is better for prevention – but it is never too late to see benefit from treatment as chronic injuries still respond well to shockwave.

Author: K. Luknowsky, BKin

Research: Dr. L. Barsalou, BSc, DC